“It’s just for the summer.” That’s what my parents told me as I boarded the train to spend three months in the countryside with my great-aunts. The city skyline faded into the distance, replaced by rolling hills that climbed high into the horizon. The gentle rocking of the train lulled me into a trance. Three months in an old house, on top of a tall hill overlooking a silent lake in a sleepy village with nothing to do, was enough to make me lose my mind.

“Great,” I said out loud to myself, my thoughts turning to the city that I was leaving behind. There was always something to do in Manhattan, whether it was going out to eat, going to a skateboard park, catching a movie or going to the mall. By the time the conductor announced Ambrosia Hill, I was the only passenger left. Me, myself, and I, all alone, a ticket for one to the last stop on the line.

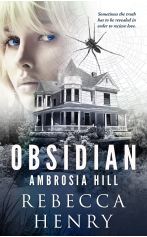

I peeked out of the window and saw the glistening ripples of Lake Cauldron. The black turrets of a tall Victorian-style house touched the clouds like a church steeple in an empty town. I could almost see both my aunts sitting on the porch overlooking their enormous garden, drinking freshly squeezed lemonade with their long black dresses, wide-brimmed hats and crimson boots. As the train rolled to a stop, I grabbed my suitcase then left the car. The station was quiet and empty, much like my plans for the summer. I swung my bag over my shoulder and rolled my suitcase to the parking lot.

I took a moment to remind myself that this was just for the summer. My old life would still be waiting for me in September with the same boring school, the same bullying kids and the same depressing apartment with my parents still on the verge of a divorce…but it was my life, and I resented being sent away from it. I brushed my long hair out of my face, wishing I could grow up by September, skip high school and be off to college, or go backward in life to when things were happier and be a little kid again. Anything would be better than being thirteen in the twenty-first century.

Charlie was waiting by his old pickup truck. The rusted hubcaps were a deeper shade of orange than the last time he had met me at the station, and I thought a headlight might be out, but overall, the car seemed functional enough. Charlie flashed me a big, fatherly smile. The wrinkles around his eyes traveled down the sides of his face, and for a moment I couldn’t believe how time had caught up to him since my last visit. “Well, look at you, Zinnia! You’ve shot up like a string bean.”

Charlie reached straight for my suitcase and threw it into the truck. His hearty laugh filled the cabin as we both buckled in. “I almost didn’t recognize you there with how you’ve grown.” I looked down at my cramped legs, desperate to stretch out as my knees touched the glove compartment. Charlie patted my back and turned the key inside the ignition, bringing life to the beat-up truck as the engine groaned like an old dog too tired to wake from its nap. “Here we go, String Bean! Off like a herd of turtles at the races.”

I cracked a smile at this, almost by accident, before wiping it away and looking out of the window. I could admit that I liked Ole Charlie. He’d been neighbors with my aunts for over forty years, and I’d known him all my life, so I thought it was safe to say that he was basically family. “Wait till your aunts get a look at you, string bean.”

I rolled my eyes as I tried, and once again failed, to conceal my smile. Every time I visited my aunts, Ole Charlie gave me a new nickname. I suppose my nickname for this summer is going to be string bean. I whispered it to myself for a test drive and annoyingly, it wasn’t so annoying.

“It’s been a few years since you and your mom visited us on Ambrosia Hill.” Charlie looked over at me with his old brown eyes full of affection. “Not ashamed to say we’ve missed you, string bean.”

Mom loved coming to Ambrosia Hill. The aunts had raised her after my grandma became sick and couldn’t take care of my mom anymore. Mom said visiting with Grandma during that time was the hardest thing she’d ever had to do, and it was a sad relief for everyone when Grandma passed away. That was the day Mom packed up a suitcase and moved to the city, where she eventually met my dad and had me. But she never forgot where she came from, and every summer she and I would come up by train to Ambrosia Hill and visit our aunts. At least until my parents started fighting.

I was nine years old when they had their first big fight and I remembered hiding under the kitchen table hugging the wooden leg, hoping that if I stayed hidden, it wouldn’t be real, and everything would go back to the way it was. But that didn’t happen, and the fighting only got worse. Mom was too ashamed to visit the aunts after that. With her marriage on the brink of divorce, she felt like a failure. She’d left home to chase her big-city dreams on Broadway, and instead of achieving that dream, she had gotten a reputable job, one where she could achieve success. But even if she didn’t live her exact dream, at least she was in the city, married and a mother. She’d had a good life before all the fighting began.

I rolled my window down and stuck my head out as we began the long slope up Ambrosia Hill. The village was named after the hill and apparently my aunts’ house was one of the first settlements on Lake Cauldron. Most people with lake houses invested in updating their homes into fancy summer getaways from the city. But not my aunts. They’d lived in their house for the majority of their lives, and they refused to change even a single detail, including their old purple porch.

My great-aunts loved purple and black, from the violet-painted siding to the ebony trimming along every window and doorframe. Even their garden was filled with purple and black flowers mixed amongst the green foliage. The house was the same on the inside, with rich black wood furnishing and purple wallpaper. My room was in the attic when I came to visit and it was a fairytale room hidden from the rest of the massive house. When I was a little girl, we’d painted the ceiling a deep indigo with pale crescent moons and diamond-shaped stars. The walls were papered in pale pink with blue roses. Pink and champagne ceiling lights hung across the attic and warm fairy lights covered every square inch of the room. An old-fashioned canopy bed with four black posts sat in the center.

Growing up, I used to pretend that I was a princess locked in a tower waiting for my one true love to rescue me. But what I didn’t admit to anyone, at least not then, was that I never wanted to be rescued by a prince. I wanted someone else, something different from what the other girls my age wanted in life, and the typical happy ending didn’t feel right to me. Fairy tales screw kids up. It wasn’t who I wanted to rescue me that was the issue—it was the fact I thought I needed to be rescued by anyone. My parents were desperate to understand what I wanted, and when they couldn’t, they started insisting that it was simply a phase, and that I’d grow out of it once I met the right boy. Truthfully, I don’t think they even had the time to worry about me. They were far too busy arguing with each other.

Still, my dad was persistent that time away with my aunts would clear my head and eventually I’d forget all about the girl from my class. The girl with the red hair and freckles who had stabbed me in the back. The girl who had been yanked out of St. Hope and enrolled into another school the second her parents discovered the letter I had written to her. A letter that had gone around my entire middle school and had labeled me forever. It had hurt at first, knowing that kids in school slapped me with a label like I was different from them. I wasn’t different—I was just me and I deserved to be myself like everybody else in the world. I wouldn’t allow some meddling bullies to affect me. I would not let them win by showing them how they’d hurt me.

As the truck stopped outside the garden gate, Aunt Stella and Aunt Luna jumped up from their rickety porch chairs and ran down the driveway to greet me. Aunt Luna was carrying a black kitten in her arms, and Aunt Stella was holding on to the top of her wide-brimmed hat, which shielded her eyes from the glaring sun. Almost unconsciously, I ran to meet them, flying into their arms. The tears that I had been holding back rushed out of me like a waterfall. They burned my flushed face as I clung to my aunts. They comforted and cuddled me like momma birds.

“It’s all right now, my darling girl. You’re with us. No one will hurt you.” I looked into Aunt Stella’s loving eyes. There with them on Ambrosia Hill, I could be me. I didn’t have to wear a mask or pretend to be strong—I could allow my tears to flow freely.

“You are our little love and always will be.” Aunt Luna cupped my face in her chubby hand, and I reached for her like a child hugging a teddy bear.

“Come now. I know exactly what you need,” piped up Aunt Stella.

“Yes, yes, yes!” clucked Aunt Luna as she handed me the black kitten. “A glass of chocolate almond milk with a chocolate chip cookie is just the thing for this occasion.” Both aunts turned on their heels and shuffled back to the house.

“Come along, dear!” called Aunt Stella. I turned and waved goodbye to Ole Charlie, who tipped his cap at me with a wink before getting back in his truck and driving away.

The purple and black walls swelled when I walked inside the dark house, then surrounded me like a giant hug and for a moment, it felt like the house was alive and greeting me with love. Nothing had changed in the three years since I had last visited. Black candles sat inside tall iron holders. Old dusty books decorated the built-in bookshelves along the far wall. Dried herbs hung from every rafter and exposed beam. Inside the large wood-burning fireplace were towers of quartz crystals. Branches of eucalyptus draped around the mantel, trailing to the floor. Wicker baskets littered the house, filled with yarn, empty glass jars and pouches of dried herbs.

I inhaled, breathing in the scent of my summer home, my other life…a part of me I had almost forgotten existed. Suddenly, I was overcome with the realization I had forgotten my true self. Standing amongst my aunts’ collection of tarot cards, pentagrams and spell books, I remembered the inner strength I had inside me. There is another identity to the Fern women, an identity my mother tried to hide from the world. Only in Ambrosia Hill were we free to be who we truly were—a lineage of magical women.

My aunts scurried back from the kitchen with Aunt Luna carrying a tray of homemade cookies and three glasses of chocolate almond milk. Aunt Stella caught me eyeballing the clutter surrounding me and placed a hand upon her hip.

“Darling girl, a clean house is a sign of a misspent life.” She raised her eyebrows to support her statement.

“Come along, dear. We have something important to do,” Aunt Luna said as she skipped past me, stopping to kiss the kitten, which was, by then, curled up like a baby in the crook of my arm.

“You won’t want to miss it, dear!” added in Aunt Stella as she raced up behind me, shoving me back out the front door and onto the porch. A tote bag was draped over her shoulder.

The aunts placed the tote bag and tray of treats onto the porch table as they chirped back and forth to one another in playful banter. “She forgot what day it is! Why, this used to be her favorite day of the summer. Apart from her birthday, that is.” Aunt Luna laughed.

Aunt Stella nodded, positioning a stack of card paper neatly on the table. “She’s been inhaling too much smog in that city. The fresh air will do her lungs some good, she’ll remember any moment now,” she replied. Her heeled boot tapped against the weathered wood floor. I sat down between them, setting the kitten on the table next to a vase of purple orchids and some black candles.

“What am I supposed to be remembering?” I could feel the creases in my forehead grow deeper as I desperately tried to recall what special day it was. My aunts both looked at me with their eyebrows raised gesturing at the random items scattered on the table in front of them. I shrugged in apology, still not grasping the significance of the day.

“It’s the summer solstice!” they sang in union.

I turned my wrist up and caught the date on my smartwatch. “Oh, my gosh, it’s June twenty-first.”

Coming from a historical line of green witches, the summer solstice had always been a significant day with an important purpose for the Fern women. Every June twenty-first, my aunts wrote about the things they wanted to let go of in their lives, things that no longer served a purpose. After they wrote their messages in gold ink, they folded the paper into a tiny boat and placed a tealight inside it. When the crescent moon appeared in the night sky, they lit the candle and released the boats into Lake Cauldron. It was a symbol of new beginnings and a chance for positive self-growth. I shook my head, amazed that I had forgotten about the summer solstice.

Both my great aunts had lived their entire lives as green witches, just as their mother and her mother before her had done, going back three hundred years. My aunts had educated me at an early age on how to be a green witch. The very essence of a green witch was to be a naturalist, someone who connected with nature on a personal and powerful level. Green witches were wise women, herbalists and healers who helped those around them by using the properties of nature. We may never use magic to harm others or for personal gain. I was a green witch by birth rite, and fourteen was a significant year for a teenage witch. I hadn’t identified as a practicing witch before. I’d never cast spells on my own. Any spells I had done were guided by my aunts. However, at fourteen, Fern witches developed individual traits and branched out into our own magic. I could feel a change coming. One that would redirect my path forever.

“Ha! She remembers! I told you she would. You worry too much, that’s your problem, Luna.”

Aunt Luna placed her hands on her round hips with her head cocked defiantly to the side. “I do not. You’re the one who worries.”

Aunt Stella waved her hand in the air. “Pish-posh. I am as calm as a cucumber, but you could worry the horns off a billy goat.”

I giggled, breaking up their banter. I reached for the gold pen and a piece of black cardstock. I stared at the paper, unable to find the words I needed to write. I could feel them stirring inside me and I could see them take form in the shape of her face.

Aunt Luna reached for my hand, understanding my internal struggle. Aunt Luna was the maternal one of the two sisters. She lived to nurture those around her, and her maternal instincts were fierce when it came to me. Although Aunt Stella was stern, she had an intense love that ran deeper than any river marked on a map, and I could feel that love surrounding me as I stared at the pen in my hand. It baffled me why neither she nor Aunt Luna ever had children of their own. I made a mental note to ask them someday.

“Draw, dear,” whispered Aunt Luna. “A picture can be just as powerful as words. If your artistic expression helps you, then draw whatever you need to let go of.”

Before I could respond, my hand moved involuntarily, sketching the outline of her face. Of all their faces, everyone who had hurt me.

Facebook

Facebook Twitter

Twitter